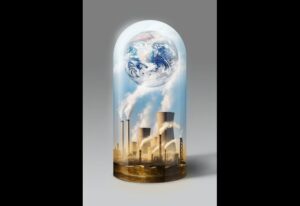

Belém, Brazil – As the COP30 climate conference concluded, Brazil’s bold offer to gradationally phase out fossil energies surfaced as one of the most debated and high-profile motifs of the peak, pressing both the country’s political intentions and the patient global contradictions girding climate action. The roadmap, supported by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, aims to produce a global strategy for reducing dependence on fossil energies, but its event underlined the deep divisions between environmental precedences and profitable interests, particularly in oil painting-producing nations.

The conception of a “roadmap to end fossil energies” was first introduced by President Lula during the Leaders’ Summit held at the opening of COP30. The action snappily came central to conversations throughout the two-week conference, sparking debates that extended beyond formal sessions into bilateral addresses, shops, and resemblant meetings involving scientists, transnational agencies, and representatives from the reactionary energy industry. Brazil’s ambition was to turn the offer into a technically predicated frame that could guide countries toward a coordinated and gradational transition from oil painting, gas, and coal, aligning with the pretensions of the Paris Agreement.

Despite the enthusiasm girding the roadmap, the offer revealed a stark contradiction in Brazil’s climate programs. Just weeks prior to COP30, the Brazilian government authorized drilling for new oil painting wells off the Amazon seacoast, a move that environmental groups and transnational spectators argued was inconsistent with the idea of phasing out fossil energies. This immediacy of policy enterprise illustrated the political and profitable challenges Brazil faces in balancing domestic energy interests with its leadership borne on climate issues.

The roadmap dominated conversations incompletely because of the absence of unequivocal reactionary energy reduction language in the formal concession textbooks. While greenhouse gas reductions, renewable energy, and adaptation measures were covered, the direct citation of fossil energies—the largest motorist of global warming—was missing. This absence elevated the Brazilian offer, making it the focal point for a wide range of actors, from environmental NGOs to government delegations, and situating it as an implicit advance in global climate tactfulness.

Throughout the conference, strong opposition surfaced from several major oil painting-producing countries, led by Saudi Arabia, Russia, and India. These nations argued that the roadmap wasn’t part of the sanctioned COP30 docket and advised against including any measures that could be perceived as obligatory reductions in reactionary energy use. Their resistance illustrated the broader pressure between energy security, profitable reliance on fossil energies, and the urgency of climate action—a dilemma that has persisted for decades in transnational accommodations.

In the alternate week of the peak, President Lula, in a tête-à-tête, returned to the Blue Zone, the defined area where formal accommodations take place, to engage with country delegates and attempt to forge agreement on the offer. Brazil pushed for the roadmap to be included in the Mutirão document, the primary political package of COP30, proposing a voluntary frame for reactionary energy reduction under the broader marquee of the Paris Agreement. The approach emphasized inflexibility, allowing countries to acclimatize the timeline and compass of phase-eschewal strategies to their domestic realities, while motioning Brazil’s commitment to global climate leadership.

The offer drew both support and review. A coalition of 29 countries, including Colombia, Chile, Panama, Germany, and Denmark, originally hovered to withhold their autographs from the final agreement unless the roadmap was incorporated. These nations framed the action as an essential signal of ambition and responsibility, stressing that any believable climate frame must include clear strategies for reducing reactionary energy consumption. Still, despite oral advocacy, the final COP30 agreement neglected any direct citation of fossil energies. Delegates eventually decided to prioritize agreement over contentious language, reflecting the enduring challenge of coordinating divergent public interests in multinational climate accommodations.

Ana Toni, CEO of COP30, stressed the scale of the disagreement in assessing the roadmap, noting that the divergence among countries was roughly balanced, with support and opposition nearly equal in measure. She explained that while some countries explosively backed the action, others claimed that addressing the reactionary energy phase eschewal was outside the accreditation of the current conference. “The score was a commodity-like 85 to 80, which we more or less linked, and as you know, it has to be 195 to 0,” Toni said, emphasizing that agreement in global climate accommodations requires near-agreement among nearly 200 sharing nations.

Despite its absence from the final textbook, the roadmap offer is extensively regarded as an emblematic achievement for Brazil. By raising the issue of the reactionary energy phase eschewal so prominently, Brazil ensured that the content entered transnational attention and deposited itself as an implicit leader in advancing further ambitious climate results. Experts suggest that the action may impact unborn Bobby’s accommodations, spur specialized collaborations between countries, and encourage investment in renewable energy technologies as nations explore pathways to reduce reliance on oil painting, gas, and coal.

The COP30 conversations also stressed the complications of aligning climate tactfulness with domestic energy programs. Brazil’s contemporaneous expansion of coastal drilling and creation of a reactionary energy reduction enterprise demonstrates the intricate balancing act that arising husbandry faces. The challenge lies in satisfying immediate profitable requirements while addressing long-term environmental imperatives—a dilemma imaged in numerous countries that depend heavily on reactionary energy earnings yet seek to meet climate targets.

Transnational scientists and specialized agencies involved in the roadmap studies underlined the significance of rigorous data, modeling, and script planning. Their analyses aim to give policymakers a realistic pathway to transition energy systems, avoid grid dislocations, and minimize profitable shocks. By engaging the reactionary energy assiduity in the dialogue, the Brazilian action attempts to produce realistic results, admitting the need for technological invention, investment, and phased approaches to achieve emigration reductions without destabilizing husbandry or communities reliant on reactionary energy sectors.

As COP30 concluded, the roadmap to phase out fossil energies remains a work in progress, representative of the global climate challenge. While it was n’t codified in the sanctioned agreement, its elevation during the Belém conference signals an ongoing trouble to attune ambition with practicality, tactfulness with domestic interests, and environmental imperatives with profitable realities. Brazil’s efforts may set the stage for unborn accommodations, technological hookups, and transnational commitments aimed at addressing the most burning issue of the 21st century: the critical need to transition down from fossil energies to guard the earth’s climate.

Brazil

Climate roadmap

COP30

Fossil fuels

Lula

Brazil

Climate roadmap

COP30

Fossil fuels

Lula