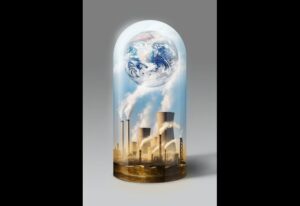

The global conservation movement is facing a challenge that receives far lower attention than niche loss, climate change, or species extermination. While conservation efforts frequently concentrate on guarding ecosystems for generations to come, numerous of the associations, systems, and strategies behind these efforts struggle to survive long enough to make a continuing impact. This quiet extremity is shaping the effectiveness of conservation work worldwide, indeed as environmental pressures continue to consolidate.

Conservation enterprises are constantly launched with urgency and idealism, driven by intimidating data and passionate individualities. New systems crop to save exposed species, restore timbers, or cover littoral ecosystems, frequently backed by short-term backing and public attention. Still, once the original instigation fades, numerous of these sweats find themselves fighting for survival. Subventions expire, patron interest shifts, and leadership changes, leaving systems vulnerable or abandoned before their pretensions are completely achieved.

Unlike diligence that measures success in daily gains or rapid-fire growth, conservation requires long-term midairs. Ecosystems don’t recover many times, and species populations may take decades to stabilize. Yet the structures supporting conservation work are frequently erected around short backing cycles and immediate results. This mismatch creates pressure on associations to prioritize visible, quick triumphs over slow, foundational work that’s essential for long-term ecological health.

One of the crucial motorists of the life problem is the way conservation is financed. Numerous associations calculate heavily on design-grounded subventions that last two to five times. These subventions frequently come with strict reporting conditions and predefined issues, leaving little room for adaptation as ecological or social conditions change. When funding ends, staff positions are cut, institutional knowledge is lost, and hookups with original communities weaken. In some cases, times of trust and structure vanish nearly overnight.

Leadership development further complicates the issue. Conservation associations constantly depend on a small number of devoted individualities whose vision and networks hold systems together. Collapse is common, driven by emotional stress, long working hours, and fiscal query. When endured leaders step down, there’s frequently no clear race plan, especially in lower associations. The result is insecurity that undermines durability and long-term planning.

Original communities, who are frequently at the heart of conservation success, are directly affected by this lack of life. Short-lived systems can produce dubitation and fatigue among residents who are constantly asked to engage, acclimatize, or change livelihoods, only to see enterprise vanish many times. This cycle erodes trust and makes unborn conservation efforts more delicate, indeed, when new systems are well-designed and well-intentioned.

The problem isn’t limited to small grassroots groups. Larger transnational conservation associations also face life challenges, particularly when operating across multiple regions. Shifts in global precedents, political changes, or profitable downturns can snappily deflect backing and attention. Systems that were formerly central can become supplemental, leaving gaps in long-term monitoring and operation. Conservation geographies, still, don’t respond well to stop-and-start approaches.

There’s also an artistic dimension to the life issue. The conservation world frequently celebrates invention and new enterprise, while long-term conservation receives lower recognition. Launching a new protected area or species recovery program tends to attract further attention than still managing one being one time after time. This bias can discourage investment in the unglamorous but essential work of monitoring, enforcement, and community engagement over decades.

Technology and data, while offering new tools for conservation, haven’t answered the life problem. Advanced tracking systems, satellite imagery, and data platforms bear sustained backing and moxie to remain effective. When systems end, outfits may fall into desuetude, and precious data can be lost or underutilized. Without long-term planning, technological earnings are threatened by getting short-lived trials rather than lasting results.

Climate change has added urgency to the question of life. As ecosystems shift and extreme events become more frequent, conservation strategies must be adaptable and flexible over long ages. Short-term systems are ill-equipped to respond to ongoing change, particularly when they warrant the stability demanded to revise pretensions and styles. Long-lived institutions are more disposed to learn from failures, acclimate approaches, and support ecosystems through inquiry.

Some conservation leaders are beginning to admit the issue and push for change. Calls are growing for backing models that prioritize long-term support, including grants, flexible subventions, and hookups that extend beyond traditional design cycles. There’s also adding emphasis on erecting original capacity so that conservation efforts can continue indeed if external backing fluctuates. Investing in people, governance, and institutions is sluggishly being honored as just as important as guarding land or species.

Education and translucency are also part of the result. Benefactors and the public are being encouraged to understand that meaningful conservation success cannot always be measured within a few times. Shifting prospects toward long-term issues may reduce pressure on associations to deliver rapid-fire but shallow results. This artistic shift could help align conservation practice with ecological reality.

The life problem remains largely implied, yet its consequences are profound. Without durable institutions, stable backing, and sustained community connections, conservation falls into the pitfall of getting a series of temporary interventions rather than a nonstop commitment. As environmental challenges grow more complex and long-term, the capability of the conservation world to endure may prove just as critical as its capability to introduce. Addressing life isn’t a distraction from conservation pretensions; it’s a prerequisite for achieving them.

Conservation

environment

Funding crisis

sustainability

Conservation

environment

Funding crisis

sustainability