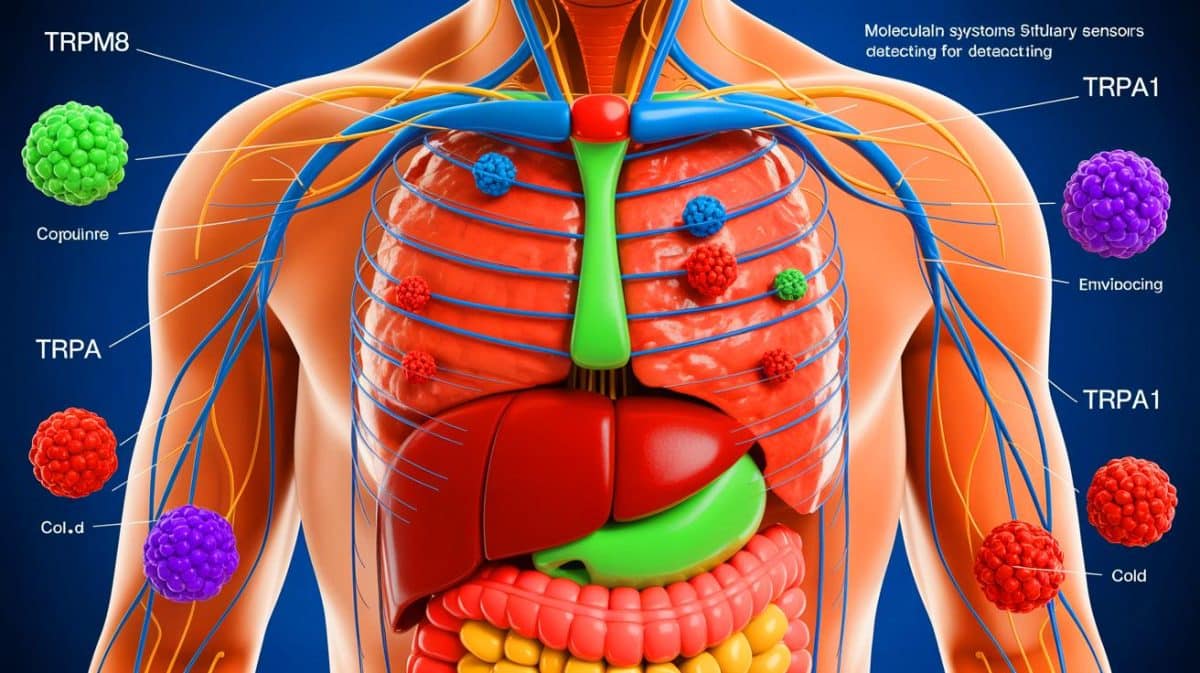

A new scientific discovery is changing the way experimenters understand how the mortal body senses cold, revealing that temperature perception is governed by two distinct molecular systems rather than a single pathway. The findings offer fresh sapience into how humans maintain thermal balance and could open new possibilities for treating cold perceptivity diseases, habitual pain, and conditions linked to abnormal temperature perception.

For decades, scientists believed that the body reckoned on a fairly straightforward medium to descry cold. Sensitive jitters in the skin were allowed to respond directly to drops in temperature and relay that information to the brain, driving sensations similar to a bite, discomfort, or pain. Still, the new study suggests that cold perception is more complex, involving separate molecular systems that serve different purposes and respond to cold in unique ways.

According to the exploration, one system is responsible for detecting mild cooling and regulating comfort, while the other responds to extreme or potentially dangerous cold. This binary approach allows the body to finely tune its responses depending on environmental conditions. A cool breath on a warm day may feel stimulating rather than painful because it activates the system linked to comfort and temperature regulation. In discrepancy, exposure to icy conditions triggers a different molecular pathway that signals peril and prompts defensive responses.

The discovery helps explain why cold sensations can vary so extensively from person to person and indeed within the same person under different circumstances. It also sheds light on why certain medical conditions beget inflated or dulled responses to cold waves. Some people witness pain at temperatures others find tolerable, while others may not feel cold at all despite being exposed to low temperatures.

Experimenters set up that the two molecular systems operate singly but communicate with the brain in reciprocal ways. The first system monitors gradational changes in temperature and helps maintain balance by encouraging actions similar to seeking warmth or conforming apparel. The alternate system acts as an alarm, quickly waking the nervous system to a potentially damaging cold wave that could harm towel health.

This distinction is pivotal for survival. By separating comfort-related cooling from dangerous cold, the body avoids gratuitous stress responses while remaining set to reply snappily to peril. The study suggests that these systems evolved to help humans acclimatize to a wide range of climates, from mild seasonal changes to extreme cold surroundings.

The findings also have significant counteraccusations for understanding diseases related to temperature perceptivity. Conditions similar to Raynaud’s miracle, where fingers and toes become sorrowfully cold due to blood vessel condensation, may involve dislocations in one or both of these molecular pathways. Also, individuals with whim-whams damage or habitual pain frequently report abnormal cold sensations, which could now be explained by imbalances between the two systems.

Beyond medical conditions, the exploration offers sapience into everyday gestures of comfort and discomfort. It helps explain why air-conditioned spaces can feel uncomfortably cold indeed when temperatures aren’t extreme, or why some people tolerate cold rainfall better than others. Differences in how explosively each molecular system responds could shape particular preferences for temperature and influence how people acclimatize to their surroundings.

The study also highlights the part of the brain involved in interpreting cold signals. While molecular detectors descry temperature changes, the brain eventually decides how those signals are perceived. Emotional state, context, and environment can all impact whether cold feels stimulating, uncomfortable, or painful. Understanding the natural basis of these sensations could help design surroundings that promote comfort, similar to workplaces, hospitals, and public spaces.

In practical terms, the discovery could lead to new treatments for people who suffer from extreme cold perceptivity or habitual pain touched off by low temperatures. By targeting specific molecular pathways, unborn curatives might reduce painful cold sensations without affecting the body’s capability to descry dangerous conditions. This perfection could ameliorate quality of life for millions of people while conserving essential defensive responses.

The exploration may also impact the development of apparel and wearable technology. By understanding how the body distinguishes between a mild and a dangerous cold, contrivers could produce garments that enhance comfort by stimulating the applicable sensitive pathways. Smart fabrics and temperature-regulating accoutrements could be acclimatized to work in harmony with the body’s natural systems.

Another important recrimination lies in aging and health. As people grow aged, their capability to smell temperature frequently declines, adding to the threat of hypothermia or injury. Understanding the binary mechanisms of cold perception could help identify why this decline occurs and lead to strategies to cover vulnerable populations.

The discovery comes at a time when climate variability is adding exposure to temperature axes. Heatwaves and cold snaps are getting more frequent, making it more important than ever to understand how the mortal body responds to environmental stress. Perceptivity into cold perception could help public health officers develop better guidelines for guarding people during extreme rainfall events.

While the exploration marks a major step forward, scientists advise that important things remain to be learned. Further studies are demanded to explore how these molecular systems interact with other sensitive pathways and how genetics influence individual differences in cold perception. Experimenters are also interested in how these systems serve in different corridors of the body, similar to the hands, face, and core.

Overall, the discovery of two distinct molecular systems for seeing cold represents a significant advance in sensitive biology. It challenges long-held hypotheticals and provides a more nuanced understanding of how the mortal body maintains comfort and safety. By revealing the retired complexity behind a sensation as familiar as cold, the exploration opens new doors to medical invention, bettered comfort, and a deeper appreciation of the body’s remarkable capability to acclimatise to its terrain.

Cold sensation

Human body

Molecular system

Temperature perception

Cold sensation

Human body

Molecular system

Temperature perception