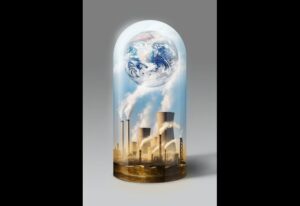

UK Unready for 2°C Climate Rise, Warns Committee

2050

Adaptation

Baroness Brown

Carbon

Climate Change Committee

Climate crisis

Climate risk

CO2

Education

emissions

environment

Flooding

Global heating

global warming

Government

Heatwaves

Methane

NAP3

Nitrous oxide

Policy

Preparedness

Resilience

sustainability

Temperature rise

UK

2050

Adaptation

Baroness Brown

Carbon

Climate Change Committee

Climate crisis

Climate risk

CO2

Education

emissions

environment

Flooding

Global heating

global warming

Government

Heatwaves

Methane

NAP3

Nitrous oxide

Policy

Preparedness

Resilience

sustainability

Temperature rise

UK

Subscribe to our newsletter

Climate Action Is an Opportunity for Growth, Not a Constraint: VP Radhakrishnan

The UK’s Climate Change Committee warns the nation is unprepared for a 2°C rise by 2050, urging stronger adaptation action.

READ MORE

Philippines SEC Adopts ISSB-Aligned Sustainability Disclosure Rules

Commending the Council for International Economic Understanding for creating the Forum as a platform for serious discussion and action, he says India’s development path over the last decade has consistently tried to balance growth with equity, and present needs with future responsibility

READ MORE

Egypt Mobilizes $750M Green Bond Finance for Climate Action

Egypt secures $750M in green bond funding to cut emissions, boost adaptation, and strengthen its Climate Strategy 2050

READ MORE

Why Soil Is Key to Solving the Climate Crisis

Ignoring soil health weakens climate action as degraded land releases carbon and worsens floods, droughts and food risks.

READ MORE

Conservation Faces a Silent Crisis of Longevity

Conservation efforts struggle to last as short funding cycles, burnout and weak institutions threaten long-term impact.

READ MORE