Soil infrequently features in climate exchanges dominated by renewable energy targets, carbon requests, and artificial emigrations. Yet beneath timbers, granges, and champaigns lies one of the earth’s most important and overlooked climate controllers. Scientists and environmental experts decreasingly advise that without guarding and restoring soil, global efforts to attack climate change will remain deficient and ineffective.

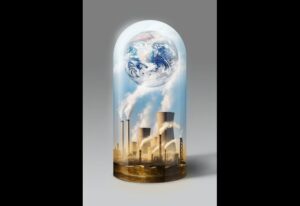

Soil is far further than dirt. It’s a living system bulging with microorganisms that store vast quantities of carbon, regulate water cycles, and support food production. Encyclopedically, soils contain more carbon than the atmosphere and all foliage combined. When soils are healthy, they act as a carbon Gomorrah, absorbing and storing carbon dioxide. When degraded, they become a source of emigration, releasing carbon back into the atmosphere and accelerating climate change.

Across the world, soil declination is happening at an intimidating pace. Ferocious husbandry practices, deforestation, overgrazing, civic expansion, and inordinate use of chemical diseases have stripped soils of organic matter. As soils lose their structure and natural exertion, they become less able to hold carbon and water. This not only worsens climate change but also increases vulnerability to cataracts, famines, and crop failures.

Agriculture sits at the center of this challenge. Ultramodern food systems have prioritized high yields and short-term productivity, frequently at the expense of soil health. Practices similar to deep plowing, monocropping, and heavy chemical inputs disturb soil structure and kill salutary organisms. Over time, this weakens the soil’s natural capability to regenerate, locking growers into cycles of advanced input costs and declining adaptability.

The climate impacts of demoralized soil extend beyond carbon emigrations. Healthy soils can absorb large quantities of downfall, reducing runoff and flooding during extreme rainfall events. Degraded soils, by discrepancy, harden and lose their capability to retain water, adding the threat of flash cataracts and corrosion. During famines, these same soils dry out snappily, leaving crops and ecosystems vulnerable to heat stress.

Despite these realities, soil protection remains largely absent from public climate strategies. While timbers and abysses are extensively honored as carbon cesspools, soil is frequently treated as a secondary issue, folded into agrarian policy rather than climate planning. Experts argue that this separation is a mistake, as soil health directly influences emigration, adaptation, and food security.

There’s growing substantiation that restoring soil could deliver significant climate benefits. Practices similar to cover cropping, reduced tillage, crop gyration, compost operation, and agroforestry can rebuild organic matter and enhance carbon storehouse. Regenerative husbandry styles, which concentrate on working with natural processes rather than against them, have gained attention as a way to ameliorate soil health while maintaining productivity.

Growers who have espoused these approaches frequently report bettered yields over time, lower input costs, and lesser adaptability to rainfall axes. Still, the transition can be grueling. Original costs, lack of specialized support, and queries about short-term returns discourage numerous growers from changing established practices. Without policy support and fiscal impulses, soil-friendly husbandry remains delicate to gauge.

Soil declination isn’t limited to cropland. Civic development seals soil under concrete and asphalt, precluding it from storing carbon or managing water. Mining, structure systems, and tips further disrupt soil systems. In numerous regions, clod that took thousands of years to form is lost within decades, with little chance of recovery.

The issue is particularly critical in developing countries, where livelihoods depend directly on land productivity. Degraded soils contribute to poverty, food instability, and migration, creating social pressures that compound environmental challenges. Climate change intensifies these problems, as extreme heat and erratic rainfall place fresh stress on formerly fragile soils.

Some governments and transnational bodies are beginning to celebrate soil’s part in climate results. Enterprises promoting soil carbon dimension, sustainable land operation, and nature-grounded results have surfaced in recent times. Still, progress remains uneven, and backing for soil restoration lags far behind investments in energy and artificial transitions.

Critics also advise against sophisticating soil’s climate eventuality. While soil can store significant quantities of carbon, it isn’t a measureless or endless result. Inadequately managed restoration efforts can fail or indeed boomerang, releasing stored carbon if practices are abandoned. This underscores the need for long-term commitment and careful monitoring rather than quick fixes.

Public mindfulness of soil’s significance remains low. Unlike timbers or wildlife, soil is unnoticeable to most people, making it harder to rally political and social support. Yet its condition affects everyday life, from food prices to water vacuity and climate stability. Bringing soil into the climate discussion requires reframing it as a participated public good rather than a niche agrarian concern.

As the world searches for effective climate results, ignoring soil is getting an increasingly expensive oversight. Reducing reactionary energy emigrations remains essential, but it’s only part of the equation. Without healthy soils to store carbon, regulate water, and sustain ecosystems, climate pretensions will be harder to achieve and further fragile in the face of dislocation.

The future of climate action may depend as much on what lies beneath our bases as on what happens in the atmosphere. Feting soil as a central pillar of climate strategy isn’t just an environmental choice but a practical necessity. Until soil health is treated with the urgency it deserves, efforts to fix the climate will remain deficient.

agriculture

Carbon storage

Climate change

environment

Soil health

agriculture

Carbon storage

Climate change

environment

Soil health